“Ponzi scheme” has become a byword for all manner of financial frauds and monetary scams. When a rapid six month collapse erased $2T (trillion) from crypto market capitalization in 2022, mainstream media outlets were quick to again label cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, Ponzi schemes.

Writing in the Chinese People’s Daily online edition, Shan Zhiguang and He Yifan, representing the Chinese Blockchain-based Services Network (BSN), claimed:

Ever since Satoshi Nakamoto released “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” in 2008, leading to the official birth of Bitcoin, the debate surrounding virtual currency (Cryptocurrency) has never stopped for a moment. [. . .] In its essence, the author believes that virtual currency is undoubtedly the largest Ponzi scheme in human history.

Can Bitcoin be legitimately described as a Ponzi scheme? If so, is it really the largest Ponzi scheme in history? In the rapidly developing world of tokenised assets and digital currencies, the answer is not as straightforward as you might think. In fact, we are faced with a Bitcoin paradox.

Click here to download a PDF of “The Bitcoin Ponzi Scheme Paradox” by Iain Davis. Powered by HIVE Digital Technologies LTD.The Origin of “Ponzi Schemes”

Click here to download a PDF of “The Bitcoin Ponzi Scheme Paradox” by Iain Davis. Powered by HIVE Digital Technologies LTD.The Origin of “Ponzi Schemes”

The Dictionary of Idiomatic English Phrases, published in 1891, claims that the etymological root of the the phrase “rob Peter to pay Paul,” meaning to take what rightfully belongs to one person to pay another, is founded in English folklore:

In 1540 the abbey church of St. Peter’s, Westminster, was advanced to the dignity of a cathedral by letters patent; but ten years later it was joined to the diocese of London again, and many of its estates appropriated to the repairs of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

There is some dispute and evidence suggesting “rob Peter to pay Paul” was in common usage before the 16th century. Later dictionary definitions specify that the phrase means “transferring money from one group of people or place to another, rather than providing extra money.”

If we apply this to bank deposits, which are bank liabilities, then bank borrowing represents a variation of the process. We could rephrase it “use the debt owed to Peter to lend to Paul.” If we then consider a fractional reserve banking system, and the likelihood that Paul’ money will also be banked, then the whole deposit, lending and debt creation process—we call it the fiat monetary system—starts to look distinctly fishy.

The idea of taking money from some to pay others, has enabled many frauds and scams over the centuries. If the prospective victims can be encouraged to forgo pecuniary caution, then the fraudsters are on to a winner. Providing their fraud isn’t exposed and they don’t get caught.

Sarah Howe opened the Ladies’ Deposit Company in 1879. Operating out of Boston, Howe offered her exclusively female clientele an enticing 8% monthly compound interest, promising to return $96 profit on an initial $100 deposit in the first year.

In a highly misogynistic society, where women’s access to finance and banking was limited, Howe pitched her banking business by appealing to women’s sense of injustice. Claiming effective charity status, she told unsuspecting depositors that she was bankrolled by wealthy Quakers and their deposits were safe. None of this was true.

No one was covering Howe’s operation. She was paying dividends to early investors directly from the deposits she had taken from her other customers. Howe’s fraud was exposed and most of the women who believed her, and in the cause she claimed to support, either lost their savings or a considerable proportion of them.

Howe served a three year sentence and, upon her release, embarked upon practically the same scam again before being imprisoned a second time. Howe’s favoured fraud would later become known as a “Ponzi scheme.”

The Ponzi Scheme Takes Shape

Less than two decades after Howe’s downfall, in 1898, William Miller, who became known to many as “520% Miller,” started an investment scheme that promised investors a huge percentage return on their initial deposit. Aged just 21, by all accounts, Miller was a poverty stricken office clerk with a young family to feed. Having failed miserably in his white collar career and with no notable blue collar skills, Miller turned to the only thing he thought he could make money from: finance.

Miller regularly frequented “bucket shops” where those on lower incomes would effectively bet on activity in the stock and commodity markets. While, in reality, no stocks or commodities were exchanged, as a “bucketeer,” Miller studied market form like racing enthusiasts study horses. Miller was hopeless at this too and regularly lost his meagre earnings in the bucket shops.

Miller somehow ingratiated himself among the flock of the Christian Endeavor Society of the Tompkins Avenue Congregational Church. He first convinced Oscar Bergstrom and two other churchgoers to invest, what was then, the not inconsiderable amount of $10 each into his insane financial proposition. Promising them a 10% weekly dividend—an annual return of 520%—Miller convinced his victims that he was such an astute investor, he could not only indemnify their initial investment but provide them easy riches in return.

If they reinvested their weekly dividend, Miller was offering them compound interest that would ultimately provide a windfall of $1,420, for their initial $10 deposit, in the first year. Anyone who understood either markets or finance would have quickly realised this was a quite ludicrous proposal. It seems Miller preyed upon people with a very limited grasp of finance. This is common feature of nearly all Ponzi schemes.

Miller’s scheme took off because he seemingly delivered. His early depositors made the returns he promised. Within months, Miller’s magic money making machine had become the talk of Brooklyn, then New York and soon the entire United States. Naming his scam “the Franklin Syndicate,” the money poured in from across the country.

Unfortunately, for most of his investors, it was all a ruse. Miller was paying dividends and cash outs from the money he had accumulated from every other investor. His gambit was to hedge that not all of his investors would cash out at the same time. While they didn’t, providing withdrawals remained relatively low, he could cover the payments. You may have spotted that Miller’s scheme was not dissimilar to fractional reserve banking in this regard.

While the Syndicate made some investments, there was no underlying portfolio that could even remotely cover any kind of run on Miller’s operation. His entire scheme was based upon perpetual and significant deposit growth. A slow down of incoming investors would leave Miller with an unsolvable liquidity crisis. The Franklin Syndicate was a fraud.

When this was exposed in the press, Miller fled to Canada before being arrested and extradited back to the US. Despite a protracted legal dispute, involving successful appeals, which were then reversed, and a dizzying array of accusation and counter-accusation among the scam’s protagonists, Miller, who was also nicknamed the “the Boy Napoleon of Finance,” was nonetheless imprisoned in Sing Sing prison. Upon his release, Miller went straight and garnered yet another moniker: “Honest Bill.”

While it seems highly likely, it isn’t absolutely clear if Carlo Pietro Ponzi, better known as Charles Ponzi, was familiar with either Howe’s or Miller’s scams. What can be said is that he emulated their model of financial fraud and took it to new heights. Consequently, he will forever be remembered for his “Ponzi scheme.”

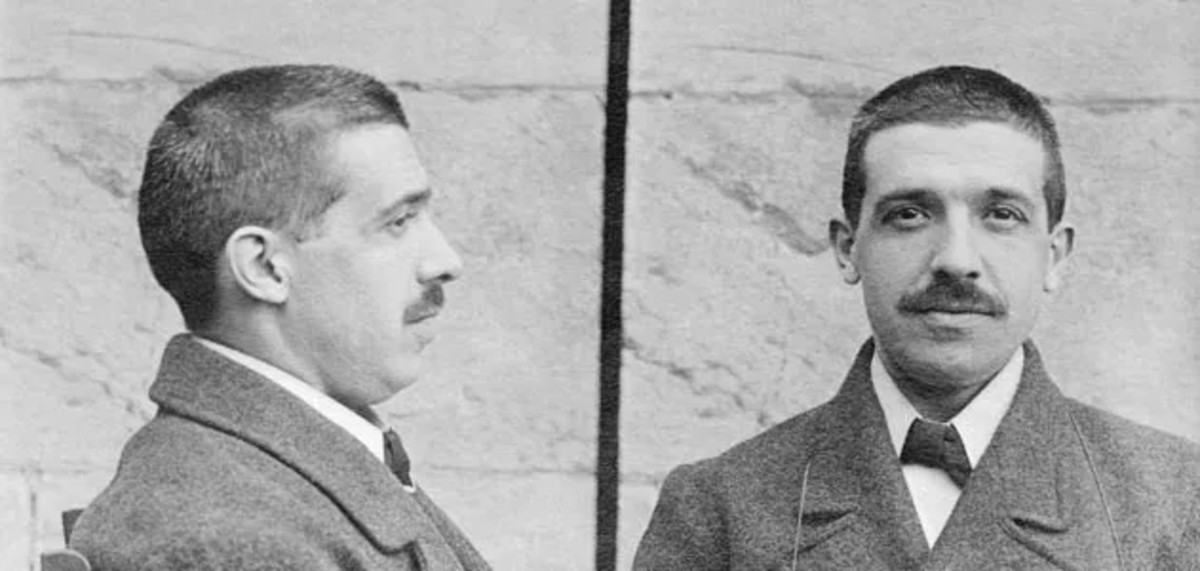

Mug shots of Charles Ponzi, Boston financial wizard, taken during his arrest for forgery under the name of Charles Bianchi. Bettmann / Corbis

Mug shots of Charles Ponzi, Boston financial wizard, taken during his arrest for forgery under the name of Charles Bianchi. Bettmann / Corbis

Born in Lugo, Italy, in 1882, Ponzi arrived practically penniless in Boston in 1903. By the time he embarked upon his Ponzi scheme, he had already been convicted for fraud, in Canada and, what we would today call, “people smuggling” in the US.

As a young man in Italy, Ponzi worked for the postal service. This perhaps influenced his decision to initially launch an entirely legal arbitrage business.

Ponzi reportedly received a letter from Spain with an “international reply coupon” (IRC) included. Ponzi noted that the IRC price paid in Spain was considerably less than the face value of the US stamp he could purchase with the it. He set about exploiting the international price difference for legitimate profit by selling foreign IRC purchased US stamps to US customers. Ponzi established “the Securities Exchange Company” for his venture.

While theoretically viable, Ponzi’s arbitrage profit margins relied upon him undercutting the US post office. His potential customers could buy the stamps practically everywhere and had no inducement to buy from him otherwise.

His margins were further restricted by unfavourable fluctuation in exchange rates, advertising costs, delivery and supply costs and he required significant trade volume to provide himself with any kind of substantial income. In other words, if he was going to earn a living from his idea, hard work was necessary. Evidently, this wasn’t something Ponzi was too keen on and his ambitions went far beyond running a small business.

Unlike Miller, who simply claimed he was a financial wizard, Ponzi recognised that he could lend some authenticity to his fraud by basing it upon, what at least appeared to be, a plausible business idea. Ponzi decided to make up some wild, unfounded claims about the success of his international arbitrage operation and focused upon attracting as many investors as possible.

Claiming the need to maintain competitive advantage, Ponzi said he couldn’t disclose the precise details of his method. A broad outline of his business plan was sufficient to convince a throng of investors. He offered them a 50% profit, first within 90 days and then later, to increase the pace of incoming deposits, within 45 days.

Ponzi’s scheme was, in all other respects, identical to Miller’s and Howe’s. Payments were made as promised to early investors from the deposits hoovered up from all the others. Healthy dividends paid to a minority convinced the majority to reinvest and never cash out, thus enabling Ponzi to rapidly expand. Taking the bulk of his gains for himself, Ponzi knew where the real money lay and so sought to buy a controlling interest in a bank.

Ponzi targeted the Hanover Trust bank which had turned down his $2000 business loan request only a year earlier. Once the fraud was finally reported by the press, in the summer of 1920, his “Ponzi scheme” collapsed in short order. Charles Ponzi’s exposure elicited a terminal run on Hanover Trust which also held a $125,000 deposit from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, leading to the resignation of State Treasurer Fred Burrell.

Ponzi’s inexorable march towards another prison sentence probably wasn’t helped when “520% Miller” was quoted by the New York Times, just days before the complete implosion of Ponzi’s company, saying:

I may be rather dense, but I cannot understand how Ponzi made so much money in so short a time.

Ponzi faced two federal indictments on a total of 86 counts of mail fraud. He served three and half years of five year term before being re-indicted for larceny by Massachusetts state prosecutors shortly after his release. Ponzi sued, claiming this was a breach of the plea bargain he had made with federal prosecutors. The effective “double jeopardy” argumentation went all the way to the Supreme Court and Ponzi lost. In between his periods of subsequent incarceration, there were appeals, stints on the run, assumed fake identities, additional Ponzi schemes and other frauds. Eventually Ponzi was deported back to Italy in 1934.

Ponzi was a flamboyant character who, despite his crimes, enjoyed some remaining popular support which dwindled as his legal disputes dragged on. But his Ponzi schemes and frauds weren’t victimless. Many people, especially in the Boston Italian community, lost their life savings to Ponzi. While accounts vary, the total estimated losses of the first named “Ponzi scheme” were between $15M – $20M. Equivalent to between $231M – £308M today.

Ponzi’s wife, Rose Gnecco, stayed loyal to him throughout his undoing. When he was finally deported to Italy, Ponzi had reportedly swindled Rose and her family out of $16,000.

Allegedly the Largest Ponzi Scheme In History

In 2021, claiming Bitcoin was a Ponzi, the Brazilian computer scientist, Jorge Stolfi, defined the five primary characteristics of a Ponzi scheme.

People invest into a Ponzi scheme primarily because they expect good profits, and:

- that expectation is sustained by such profits being paid to those who choose to cash out. However,

- there is no external source of revenue for those payoffs. Instead,

- the payoffs come entirely from new investment money, while

- the operators take away a large portion of this money.

Ponzi schemes are always too good to be true. A modicum of due diligence should deter those wary enough to exercise some. Regardless of Stolfi’s arguments about Bitcoin—we’ll examine them in more detail shortly—in order for a Ponzi scheme to succeed, in addition to a degree of financial gullibility, the investor falls prey to the fraudster because they “expect good profits.”

So while there are victims, the individuals who lose their shirts aren’t entirely “blameless.” They exhibit what former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan called “irrational exuberance.” Obviously, this in no way exonerates the fraudster.

That didn’t stop Bernie Madoff—perhaps the most notorious exponent of the Ponzi scheme other than Ponzi himself—from levelling the accusation of greed at his victims. In March 2009, Madoff pleaded guilty to 11 federal charges, including money laundering and securities fraud, and was sentenced to 150 years. He died in prison in 2021, aged 82.

Following his conviction, Madoff’s family suffered a string of tragedies. In 2010, Bernie’s son Mark committed suicide. In 2014 his other son, Andrew, died from a very rare form of cancer and, in 2022, Bernie’s elderly sister, Sondra Wiener, and her husband Marvin both died in an apparent murder-suicide.

It is frequently stated that Madoff operated the largest Ponzi scheme in history. For reason’s we’re about to discuss, that claim is dubious.

Madoff served as Nasdaq’s chairman in 1990, 1991 and 1993, and was arrested in 2008. By then his Ponzi scheme had been running for at least 20 years and prosecutors estimated the scale of his fraud, based upon 4,800 known client accounts, to be $65B. The total lost principle was finally estimated at $19.4B. Unusually, for a collapsed Ponzi Scheme, nearly $15B of the principle has been recovered for some investors.

The US Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) protects investors against losses to fraud, but only if they unwittingly invested directly in the scam. Unfortunately, 80% Madoff’s Ponzi scheme victims came from “feeder funds” or investment pools and were deemed third parties. As such, many of the relatively small investors were not eligible for SIPC protection. Larger depositors, such as institutional investors, were relatively well protected and have retrieved most of their investment, though not their profits.

Those who withdrew more than they put in—net winners—were required to repay the difference. This left the vast majority of Madoff’s small-time victims scrabbling to file civil action lawsuits to try to recoup lost savings. Often they were trying to access the protection fund repaid to the US State by the very pools they had invested through. The big feeder funds themselves were largely covered by the SIPC.

While Madoff maintained he was solely responsible, obviously such a monumental Ponzi scheme involved many players. In subsequent years, a few faced punishment. For example, Frank DiPascali, Madoff’s chief financial officer and Madoff’s secretary, Annette Bongiorno, alongside his operations manager, Daniel Bonventre and accounts manger, Joann Crupi, all served time after related prosecutions. Others were more fortunate, financially speaking.

The investor Jeffrey Picower had grabbed an estimated $7.2B from the Ponzi scheme. As with so many others closely related to Madoff’ fraud, he died unexpectedly shortly after Madoff’s conviction. While his widow was subsequently compelled to forfeit the money, Picower certainly benefited in his own lifetime.

Stanley Chais funnelled his clients investments into the Ponzi scheme for decades. Taking an estimated $1B in profits, the celebrated Israeli philanthropist finally settled a “profit” repayment of $277M.

Norman Levy had been investing in the Ponzi scheme since the 1970s. His estate settled for $220M in 2010. Given the lengthy period of his involvement, this also seems like a rather favourable outcome.

Madoff began his scheme with seed money from clothing entrepreneur Carl Shapiro. Shapiro had been investing with Madoff for 40 years and made a $250M investment only weeks before the scam detonated. Shapiro paid back $625M in total. Picower, Chais, Levy and Shapiro eventually became known as “the Big Four.” Relatively speaking, their “losses,” if they had any, seemed more bearable than most.

Madoff founded the Wall Street firm Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC (BMIS) in 1960. Like Ponzi, Madoff’s unique selling proposition (USP) didn’t appear too outlandish. He went further than other Ponzi operators to scrupulously maintain plausibility. He gave his scam an air of exclusivity, initially declining would-be investors. He also cultivated his image as a trustworthy philanthropist, donating generously to worthy causes and didn’t offer obviously ridiculous returns.

Claiming that he used a split-strike conversion, or collar, investment strategy, Madoff convinced prospective clients that by purchasing both out-of-the-money (OTM) ‘put’ options and selling ‘call’ options (covered calls) he could assure a steady, low risk 20% annual return on investment (ROI).

If the stock value in Madoff’s portfolio dropped, the purchased put option, forcing a sale at the subsequent above market strike price, would mitigate any losses. If the price rose above the covered call strike price, Madoff’s call option buyers would exercise their right to buy his stocks.

While this would limit profits to the strike price of the covered call, the premium from selling the call options would also fund the purchase cost of the puts. Even for those with some grasp of market finance, it all seemed so believable.

Click here to download a PDF of “The Bitcoin Ponzi Scheme Paradox” by Iain Davis. Powered by HIVE Digital Technologies LTD.SEC Disinterest

Click here to download a PDF of “The Bitcoin Ponzi Scheme Paradox” by Iain Davis. Powered by HIVE Digital Technologies LTD.SEC Disinterest

Unlike Howe, Miller and Ponzi, Madoff did not promise instant riches or make conspicuously exorbitant claims. This undoubtedly contributed to the longevity of his grift, but it wasn’t the only reason he sustained the so-called “largest Ponzi scheme in history” for more than two decades.

Sixteen years before Madoff’s flimflam was exposed, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) investigation of a Florida investment pool, run by the accountants Frank J. Avellino and Michael S. Bienes. The pair were suspected of swindling $440 million out of the Florida community through their A&B trading enterprise.

But when the court appointed auditors checked A&B’s books, the money, at least, was all in place. Technically, the pair didn’t appear to be defrauding anyone. Frank and Michael were taking a profit—effectively a substantial handling fee—after outsourcing their investment strategy to a money manager. That broker was Bernie Madoff.

Madoff had pioneered electronic trading, calling it “artificial intelligence.” In 1992, as the SEC were investigating A&B, BMIS could execute trades faster and cheaper than anyone else. Consequently, BMIS’ daily trade volume was around $740M, representing 9% of all activity on the New York Stock exchange. Despite many years during the 1980s, when market volatility left money mangers struggling to even match the turbulent performance of the S&P 500 index, BMIS were seemingly always able to beat it by some margin.

US United States Securities and Exchange Commission, Kristina Blokhin – stock.adobe.com

US United States Securities and Exchange Commission, Kristina Blokhin – stock.adobe.com

When the WSJ quizzed Madoff about A&B’s pool, he revealed that he had been operating his split-strike and similar strategies, such as convertible arbitrage, since the late 1970’s. In hindsight, suggesting something closer to a 40 year Ponzi scheme.

A&B’s mistake was not registering the trades with the SEC. Had they done so, then Madoff would necessarily have been listed as their broker. The SEC accused Frank and Michael of running “an unregistered investment company [that] engaged in the unlawful sale of unregistered securities.” Speaking about A&B, Madoff reportedly said “he didn’t know the money he was managing had been raised illegally.” Everyone seemed happy to accept him at his word.

For some reason, despite a lengthy investigation and court orders compelling the A&B to return investors’ money, neither A&B’s lawyers nor the SEC named Madoff. It was the WSJ that reported the identity of A&B’s mysterious money man. Apparently, the revelation didn’t even vaguely pique the SEC’s interest in BMIS.

Ironically—perhaps having read the WSJ article—following the closure of A&B, and now knowing who the duo’s broker was, nearly all of A&B’s clients reinvested their money in BMIS’ split-strike wheeze. As did Frank Avellino and Michael Bienes.

Madoff’s Ponzi scheme had a better USP than any before it. It was a total charade nevertheless. Madoff was following the Ponzi method precisely.

He Madoff was simply depositing his investors money in his account held by Chase Manhattan Bank—later merging into JP Morgan Chase & Co—and paying client redemptions from those funds. The impact of the Ponzi scheme’s collapse was devastating for some, but not everyone. At its peak, Madoff’s account held $5.5B.

The split-strike conversion is a perfectly legitimate approach to investment. It is also a conservative, long term investment strategy unlikely to deliver an annual 20%..

Related Content

- Gate.io Crypto Arbitrage Bot Tutorial (Crypto Arbitrage Trading)

- Tonkeeper to Binance Transfer Tutorial (How to Send Crypto from Tonkeeper)

- TronLink Wallet Tutorial (Tron TRC20 Wallet Full Setup Guide)

- Australian Police Seize $9.3M in Crypto, Bust Mastermind Behind Ghost Platform

- Former US President Donald Trump Selling ETH Worth Millions of Dollars, Analysis Indicates